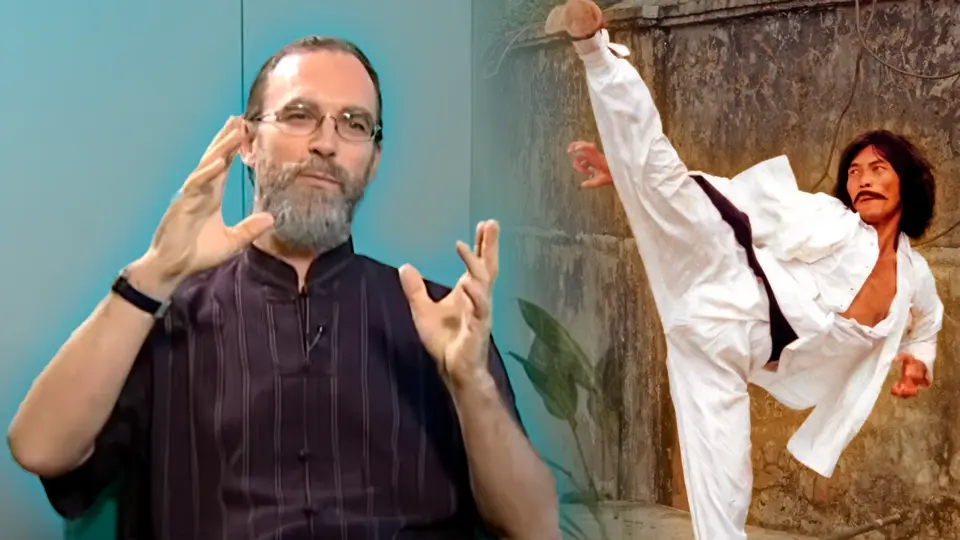

Чем больше я узнаю об индонезийском боевике Гарэта Эванса “Мерантау”, тем больше он меня восхищает. Фильм посвящен боевому искусству, которое редко увидишь на экране – Силату. Режиссёру удалось найти непревзойдённого мастера этого стиля, Ико Ювайса (Iko Uwais), подобрать отличный актёрский состав и создать на основе этого сюжет. В “Мерантау” отлично сбалансированы действие и драма, персонажи и поединки, и всё, что мы видели до сих пор из постановки и хореографии, очень впечатляет. Эванс со своей командой регулярно публикует рабочие видеоролики со съёмочной площадки, демонстрирующие актеров, хореографию, тесты камеры и поединки. И если фильм получится таким же красочным, то Эвансу впору заняться привлечением туристов для заработка дополнительных денег, потому что лично мне уже хочется туда отправиться.

Не так давно режиссёр/ сценарист Гарэт Эванс и звезда Ико Ювайс оказали нам любезность и уделили немного времени, свободного от съёмок, для обсуждения фильма. Хотите узнать, как это – снимать фильм о боевых искусствах в Индонезии? Тогда читайте.

- ТБ – Тодд Браун

- ГЭ – Гарет Эванс

- ИЮ – Ико Ювайс

Гарэт Эванс

ТБ: Если я не ошибаюсь, Вы родом из Британии, а не Индонезии. Как парень из Великобритании начал снимать индонезийский фильм?

ГЭ: Это длинная история. Моя жена – наполовину индонезийка, наполовину японка. После свадьбы мы некоторое время жили в Великобритании, с 9 утра до 5 вечера я работал, обдумывая свой будущий проект, после моей первой малобюджетной картины “Следы” (Footsteps). Позже, меня неожиданно наняли на должность вольнонаемного режиссёра в Christine Hakim Films для съёмок документального фильма, снимающегося в то время в Индонезии. Поэтому мы с женой временно проживали и работали у неё на родине, в Джакарте, а я тем временем разобрался в сути и набирался опыта в индонезийской кино- и телевизионной индустрии. После 6 месяцев работы, мы решили уехать из Великобритании и попытать счастья здесь. Полгода я работал в телевизионной компании, занимался постпроизводством и концепциями некоторых программ, но пребывание в тесном офисе меня ограничивало, и с опытом и знаниями о Cилате, которые я приобрёл во время документальных съёмок, я решил написать сценарий к “Мерантау”.

ТБ: А что связывает лично Вас с самим фильмом и боевыми искусствами? Почему Вы стремитесь сделать фильм таким детализированным?

ГЭ: С самого детства я всегда мечтал о карьере в кино, а все началось с азиатских боевиков. После просмотра на видеокассетах “Доспехов Бога” (Armour of God), “Проекта А” (Project A) и “Полицейской истории” (Police Story) я тянул своих друзей на задний двор с желанием повторить трюки Брюса Ли и Джеки Чана (к счастью, в то время ни у кого из нас не было видеокамеры, поэтому не осталось ни одной записи, над которой можно было посмеяться). По своей природе, я был тщеславным ребенком и всегда хотел исполнять роль Джеки Чана или Брюса Ли, но я ничего не понимал ни в боевых искусствах, ни в актерском мастерстве, и решил вместо этого заняться написанием сценариев и режиссурой. На 18-летие мне подарили маленькую видеокамеру и после 10 лет выдумок и идей у меня, наконец, появилась возможность записать их на плёнку. Я родом из маленькой деревни в Уэльсе и до тех пор, пока не поступил в университет, у меня не было доступа к монтажному оборудованию. Всё, что я снимал, приходилось монтировать с помощью двух видеомагнитофонов и кнопки “Пауза”, и можно только представить, какое там было качество. Позже, в университете, я начал играть с “игрушками” покрупнее. Мне захотелось пройти курс и узнать всё о кино и телевидении, но, как оказалось, он больше был посвящён компьютерам и электронике, поэтому я воспользовался своим преимуществом доступа к мультимедийному оборудованию и начал сам изучать различные техники съёмки, одновременно подыскивая способ вставить созданное видео в любую возможную диссертацию.

Я всегда был поклонником азиатского кино, поэтому моей первой серьезной короткометражкой стала история о самурае, которую я снимал в Уэльсе с помощью японских студентов, обучающихся в то время в Кардифе (Cardiff). Снимался он за мои средства и возможности были ограничены, но полученный в этих съёмках опыт дал мне почувствовать сладкий вкус режиссуры, как серьёзной профессии. После этого, я несколько лет работал в офисе, а потом решил попробовать себя в создании полнометражного фильма. Мне повезло, что мой начальник меня понял и предоставил выходные для съёмок “Следов”.

ТБ: Чем я был действительно удивлён, когда просматривал видео о создании фильма, так это Вашим вниманием к персонажам и сюжету. В большинство боевиков стараются вставить так много драк, насколько это возможно, почему бы не сделать то же самое?

ГЭ: Прежде всего, я поклонник боевиков. Я могу сидеть и смотреть фильмы часами, но что случится, когда я захочу их посмотреть во второй раз? Я перематываю драматические моменты потому, что чаще всего они просто скучны. Сюжет недостаточно продуман, а персонажи и экранные перипетии настолько ничтожно продуманы, что просто ведут от сцены к сцене. Но из “Мерантау” мне хотелось сделать фильм, который был бы не просто боевиком, но и драмой, я над этим работал и, надеюсь, что мне удалось создать запоминающихся персонажей и сюжетную линию, которые заинтригуют зрителей, и им не захочется при повторном просмотре перескакивать через эти моменты.

Для меня очень важно было уделить все возможное внимание не только боям, но и этим драматическим эпизодам. Иногда, при просмотре какого-нибудь фильма, вы с легкостью можете заметить, что когда режиссёр находиться на автопилоте, постановка поединков будет выглядеть великолепно и захватывающе, а вот драматические моменты выглядят так, будто сняты с первого дубля. Мне хотелось преподнести Ико не только как мастера боевых искусств, но и как актёра. С момента начала съемок он вырос из водителя телефонной компании до уровня настоящей потенциальной звезды. У него множество талантов и они улучшаются день ото дня.

ТБ: Вы выбрали для съёмок стиль, который редко можно увидеть на экранах. Почему Силат? Каким образом Вы создадите баланс между аутентичностью и кинематографическим качеством? Настоящие бои против работы с тросами?

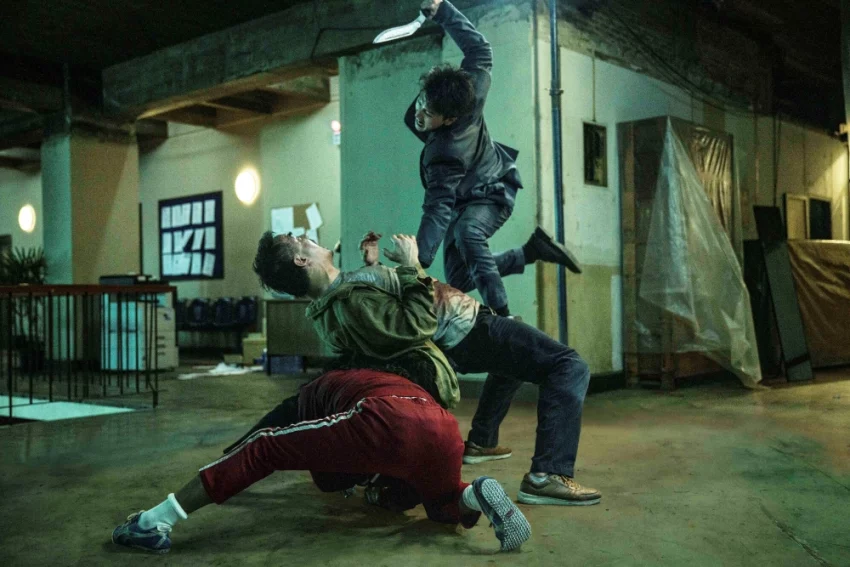

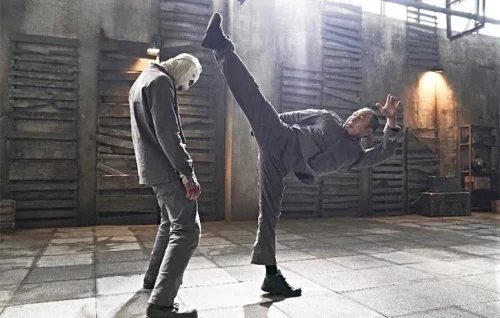

ГЭ: Я выбрал Силат после работы над документальным фильмом. Мне никогда ранее не приходилось его видеть, а после просмотра огромного количества фильмов о единоборствах, оказалось, что это уникальный боевой стиль. Позже, когда я начал сам изучать его со своим учителем (Эдвел Датук Раджо Гампо Алам | Edwel Datuk Rajo Gampo Alam – постановщик боёв в фильме), я просто обязан был, как режиссёр, сделать всё возможное, чтобы привлечь к Силату международное внимание, и, поскольку я сам живу в Индонезии, одновременно отобразить хотя бы небольшую часть индонезийской культуры и жизни. Чтобы добиться аутентичности и кинематографического качества, мы решили использовать камеру естественным способом, без круговых полетов с использованием кранов и навязчивых движений. Вместо этого мы снимали с видом наблюдателя, в частности финальный бой между Юдой, Рэтгером и Люком (двое против одного, продолжительностью 5 минут). Я часто использовал камеру “steadicam” (как в фильме Tom Yum Goong) и все бои плавно снимались от эпизода к эпизоду, чтобы избежать ненужных нарезок для каждого удара. Замедления и моменты с повторами использовались только при погонях и работе каскадеров, нам не хотелось делать бои излишне стильными, а наоборот, придать реализма, поэтому в фильме не будет тройных сальто и кувырков перед ударом ногой. Это просто не впишется в сюжет и будет не к месту, мы показали “чистый” Силат, без всякой акробатики.

Говоря о тросах, то они использовались, но очень редко и лишь в случаях, когда была необходима их помощь. Мы снимали по-настоящему, а их использовали только во время съёмок некоторых трюков (на верхушке контейнера, кувырок на мотоцикле и эпизод с прыжком из здания на здание). Нет никаких полетов и антигравитации, провода задействовались для большего контроля и обеспечения безопасности нашей команды каскадёров.

ГЭ: Все именно так, как Вы сказали. Фильмы такого стиля, насколько я знаю, не выходили в Индонезии на протяжении последних 20 лет, поэтому большинство подобных вещей появляется на экранах только в виде телевизионных шоу, которые базируются на мистицизме, эффектах и трюках с проводами. Нам действительно пришлось начинать с основ, работать не только с бойцами и каскадёрами, но и заботиться о камере и съёмках поединков. Перед тем, как написать сценарий к “Мерантау“, во время работы над документальным фильмом я снял несколько коротких эпизодов с участием бойцов Силата, чтобы придумать, каким образом подобное можно вставить в фильм и как преподать это в самом выгодном свете. Пенчак-cилат, по существу, представлен множеством форм и был создан ради чисто эстетических целей, поскольку движения больше напоминают танец, но меня больше интересовало практическое применение Силата в жизненных ситуациях. Мы придумали бои, которые были бы максимально приближенные к реализму, и решили снимать в таком стиле, чтобы можно было отчетливо разглядеть хореографию. Есть одна вещь, которая меня раздражает больше всего в фильмах, посвященных боевым искусствам – когда я вижу, как главный герой размахивает руками, ногами или оружием, и все это снято крупным планом с заполняющими пробелы в движениях звуковыми эффектами, своеобразный обман зрителя. Это примитивно и недостойно уважения. Мы сознательно решили избегать подобного в каждом бое, который снимали.

ТБ: Что было самым трудным для Вас, как режиссёра?

ГЭ: Сложнее всего было снимать бои. До этого я снимал драмы, и мне не впервой работать с иностранными языками, но что касается фильмов о единоборствах – приходилось сидеть за монитором и следить, всё ли было снято правильно, а потом надеяться, что всё будет смонтировано, как задумывалось. Во время дублей у нас были свои редакторы, занимающиеся плёнкой, чтобы я мог на месте убедиться в том, как эпизоды соединяются друг с другом, но снимать такое – это очень трудоёмкий процесс. На каждую сцену уходило минимум 15 дублей: то камера была немного не в том месте, то постановка боя не такой чистой, как мы надеялись, и этот изнурительный процесс мог продолжаться целый день. Но, после всего, пересматривая всей командой отснятые бои, мы понимали, что оно того стоит. Очень приятно слышать одобрительные возгласы и аплодисменты, когда дубль был снят удачно, но еще более приятно будет услышать возгласы и аплодисменты зрителей, когда фильм наконец-то будет выпущен.

Спасибо вам ваши труды. Энтузиазм бесценен. Об экшне мало ресурсов. И ваша популяризация необходима…

С новым годом Вас всех, причастных к этому каналу, что я читаю уже больше…

Сложно сказать где бы Марко Сарор плохо смотрелся.)

В роли Крэйвена хорошо бы смотрелся Марко Сарор. Высокого роста, атлетичный, хорошо двигается. 100%…